Entry G1: Connected Entities

The last post was the 52nd entry, meaning that I averaged one entry a week for an entire year. Now, just a little under a year into my chronicling journey, I find the need to shift focus.

My plan was to continue through ensemble models and on to SVMs and other supervised learning models. Then I’d move to unsupervised learning and look at things like clustering and dimensionality reduction. Only after that did I plan to move on to graph topics. However, I find myself spending more and more time with graph and less with pure machine learning modeling.

As such, I’ve decided to detour to graph topics and will return to machine learning at a later date. I created a new tag “machine learning” so it’ll be easy to find all the entries in the machine learning track despite this interruption.

The Problem

I need to find highly connected entities that share the same or similar information. A use case for this is any example where customers provide information. It’s common for them to give information that is slightly different, causing them to appear multiple times in a data set.

For example, I used to work in insurance and when people moved, they’d often change their agent to a local one (as they should - insurance regulations vary from state to state). So while our customer may be listed as “Patricia Jones” with her old agent, the new agent records her as “Pat Jones.” Now we have poor Patricia listed twice (and potentially charged twice until her old policy is cancelled).

This kind of duplicate detection is called entity resolution (ER). This isn’t the exact problem I’m trying to solve, as the entities I’m trying to find are a groups of people working together, but it’s the closest analogy I can think of.

Challenges

Challenges with entity resolution include:

- Attribute ambiguity: There are only so many combinations for any given attribute. Take names for example. At one employer, there were three people with the same first and last name as me. I got so tired of getting their emails that I threw my middle initial into my email address - then no one could find me ;-).

- Changing data: People move. They change their phone numbers. When the junk mail gets too bad, they just get a new email address. Or, like my example in name ambiguity, they get tired of getting the email, mail, or whatever for someone with the same name and they change that.

- Missing data: If you’ve worked with real-world data you know that unless the field is required, it’s often left blank. Hard to resolve entities when most of their attributes are empty.

- Data formatting: Any field that hold concatenated information will be prone to this problem. Example: Dates. Need I say more? The day, month, or year can come first, second, or last. You can include leading 0s (01 vs 1) in the month or day. You can have a four digit year or a two digit year (1922 vs 22). You can use numbers or spell stuff out (01 vs January, 06 vs Friday). You can even vary punctuation (01/01/1988 vs 01-01-1988 vs 01.01.1988 vs January 1, 1988 vs Jan. 1, 1988).

- Abbreviations: This is especially challenging with addresses. “Suite” can be abbreviated as “Ste”. Don’t even get me started on “street” (“Street”, “St”, “St.”, “street”, “st”, “st.” - capitalization and punctuation can throw you a curveball if you haven’t accounted for them).

Side note, if you’re interested, I discuss the different kinds of missingness in Entry 12.

The Options

There are many ways to solve entity resolution type problems. These are the ones I considered:

- Fuzzy matching

- Pariwise matching

- Clustering

- ER algorithms

- Graph

Fuzzy Matching

One of the easier solutions would be to pair fields and check the ones that are very similar. So “Patricia Jones” and “Pat Jones” are very similar and if they have the same address we can deduce that they are the same person (which isn’t a very good assumption. For example, Pat could be Patricia’s son. Even when the names are exactly the same, you still get instances where one is Jr and the other is Sr but none of your records tell you that).

Pairwise matching

We could just compare all fields between two entities and link the pairs where most fields match. For example, if Patricia Jones and Pat Jones share the same address, phone number, and email address they’re probably the same person.

This is also a dangerous deduction as Patricia and Pat may in fact be a married couple or parent/child. In these cases, they would live together and it makes sense for them to have the same contact information. However, they’d be completely different people.

We could also have a situation in which Patrica Jones just sold her house and the new owner is Pat Jones.

Clustering

With this approach, we’d cluster similar entities. This may work well for my specific case where I’m attempting to find groups of people that are working together. However, in my experience, there are often clusters that overlap, which would have to be resolved before you can action off it.

ER algorithms

My, admittedly brief, perusal of ER algorithms revealed that they’re mostly some kinds of duplicate detection that resolve the duplication by either deleting, merging, linking, or simply matching entities.

Graph

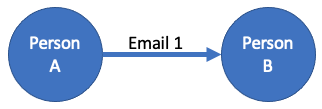

This method connects entities using some type of relationship. Entities and their relationships can be set up multiple ways, which I’ll go into more detail in a future entry. But the basic concept using then Enron email dataset as an example is Person A is an entity. Person A sent Email 1 to Person B. Person A would be connected to Person B via the relationship of that communication.

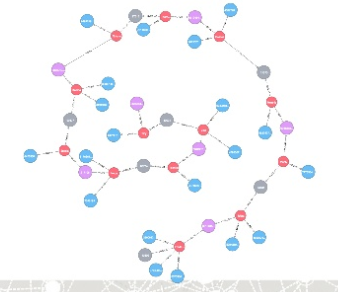

While it looks extremely simplistic, these relationships can reveal very pertinent information as demonstrated in this example from Max De Marzi’s Fraud Detection slideshare, where John and Karen share the same social security number:

The Proposed Solution

We all know what the proposed solution is, right? I mean, I did give it away in the intro: Graph. Did I really consider the other solutions or did I just find options to compare it to? I’ll leave that for you to decide.

My initial choice to explore Graph revolved around two of the challenges listed in the The Problem section: missing data and changing data. As pointed out in that section, any field that isn’t required is often left blank and customers routinely change their contact information.

Missing data can also be a challenge when comparing diverse channels. For example, a store can take orders online, over the phone, or in-person. The online channel will have information about browsers and IP addresses; the phone channel will have a telephone number; the in-person channel may include cash only transactions for which we’d have zero information on the customer. If we get a mailing address for the phone and internet orders, we still stand a chance of connecting related entities.

This kind of sparse data sleuthing can be seen in another image from Max De Marzi’s Fraud Detection slideshare:

In addition to being able to handle missing and changing data, graph allows me to use multiple techniques including graph metrics/analysis, community detection, centrality algorithms, shortest path traverses, tours, clustering coefficients, K-cores, and more.

In the Graph series of entries, I’ll work my way through this challenge and tackle these techniques one by one.