Entry 21: Scoring Regression Models - Theory

I need a way to measure a model’s performance. To do that, first I need to break it down by the type of prediction.

The Problem

Supervised learning, wherein predictions are made with the help of labelled data, tend to come in two flavors. The first is to predict a continuous number (like the price of a house - the predictions would be things like 104,684.54). The second is a class (like whether a customer is likely to purchase a product - yes or no). The prediction depends on the target values. When the target is continuous so is the prediction. When the target is a class, so is the prediction.

I’m going to look at measures for continuous targets first.

Concepts

There are quite a few terms and concepts that the solutions to this problem rely on. Since I appreciate when terms are clearly defined instead of left to the imagination, here is a list with definitions and equations.

Symbols

- $y_{i}$ is an observed value

- $\hat{y_{i}}$ is a predicted value

- $\bar{y_{i}}$ is the mean value

- $\mu$ is also the mean value

- $n$ is the number of observations

- $\sum$ means to sum (add) things together

- $\lvert x\rvert$ is to take the absolute value (of

xin this case) - The rest should be basic mathematical symbols

Bias and Variance

Hands-On Machine Learning has a very succinct sidebar with information on bias, variance, and irreducible error. These are the three components that make up a model’s generalization error.

Bias

This part of the generalization error is due to wrong assumptions, such as assuming that the data is linear when it is actually quadratic. A high-bias model is most likely to underfit the training data.

Variance

This part is due to the model’s excessive sensitivity to small variations in the training data. A model with many degrees of freedom (such as a high-degree polynomial model) is likely to have high variance, and thus to overfit the training data.

Irreducible error

This part is due to the noisiness of the data itself. The only way to reduce this part of the error is to clean up the data (e.g., fix the data sources, such as broken sensors, or detect and remove outliers).

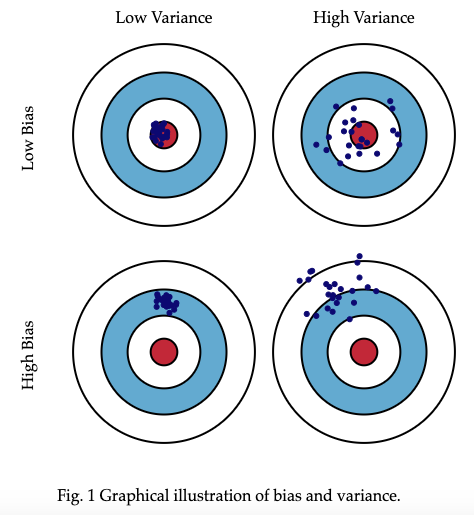

A visual reference for bias and variance from Scott Fortmann-Roe’s Understanding the Bias-Variance Tradeoff.

Bias

Bias is the difference between the expected value and the true value.

In the picture above, this means how close (low bias) or far (high bias) the values are to the bulls eye.

Variance

Variance measures how far a set of numbers are spread out from their average value. The formal definition is: the average of the squared differences from the mean.

$Var = \frac{\sum{(x - \mu)}^2}{n}$

In the picture above, this means how close (grouped together) or far apart (scattered around) the points are from each other.

Residuals

Also called error. Residuals quantify how far off a prediction was from the actual value. If the value is 0 the prediction matched the observed value perfectly. There is no minimum or maximum range. The larger the value, the further the prediction is from the actual value.

The formula is the observed value minus the predicted value:

$e = y_{i} - \hat{y_{i}}$

Keep in mind that the impact of how large this number is depends on the variance of the underlying data. For house prices that range from 100,000 to 10,000,000 a residual of 10,000 would be considered good. However, for a bottle of soap where the prices range from 0.99 to 20.49, a residual of 10,000 would be a really bad prediction.

Example of residuals from Wikimedia Commons Residuals for Linear Regression Fit. The black lines show the residual of the prediction (the red linear fit line) to the observed value (the dark blue dots)

Absolute Error

Technically, the distinction between a residual and an error is that residuals are the difference between the observed value and the predicted value, whereas errors are the difference between the observed value and the true value (ex: the true height of a person may be 5.68741878 feet, but the observed/recorded value would be 5’5”. See Errors and residuals on Wikipedia, the answers to this StackExchange question, and the definition of Mean Absolute Error on Springer Link for more information).

According to one of the answers on StackExchange: “Error term is a theoretical concept that can never be observed, but the residual is a real world value[…].”

The practical use of the absolute error in machine learning is:

$absolute\text{ }error = \lvert y_{i} - \hat{y_{i}}\rvert$

Squared Error

$squared\text{ }error = (y_{i} - \hat{y_{i}})^2$

The Options

While the three definitions above (residuals, absolute error, and squared error) applied to each individual prediction, there are other methods that measure a model’s overall performance. These methods include:

Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

This sums the absolute errors of all predictions and divides by the number of observations (or multiplies by the reciprocal of the number of observations). I.e., it gets the mean of the absolute errors.

$MAE = \frac{\sum \lvert y_{i} - \hat{y_{i}}\rvert}{n} = \frac{1}{n} \sum \lvert y_{i} - \hat{y_{i}}\rvert$

Sum of Squared Errors (SSE)

Also known as the residual sum of squares (RSS) and the sum of squared residuals (SSR). This is just adding up the squared errors for all the predictions.

$SSE = \sum (y_{i} - \hat{y_{i}})^2$

Mean Squared Error (MSE)

This basically takes the sum of squared errors and divides by the number of observations (or multiplies by the reciprocal of the number of observations) to give the mean.

$MSE = \frac{\sum (y_{i} - \hat{y_{i}})^2}{n} = \frac{1}{n} \sum (y_{i} - \hat{y_{i}})^2$

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

By now I can guess that this is just the square root of the MSE, but I looked it up just to be safe (Hands-On Machine Learning pg 37). The purpose of taking the square root of the MSE is to put the result back into the same units as the original data (Applied Predictive Modeling pg 95).

$RMSE = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n} \sum (y_{i} - \hat{y_{i}})^2}$

$R^2$ or coefficient of determination

Per Applied Predictive Modeling page 95:

Proportion of the information in the data explained by the model

- There are multiple ways to calculate $R^2$, but the one used by Scikit-Learn is:

$R^2 = 1 - \frac{\sum{(y_{i} - \hat{y_{i}})^2}}{\sum{(y_{i} - \bar{y_{i}})^2}}$

An easier to read version is:

$R^2 = \frac{MSE}{Var_{yactual}}$

- Range of values is generally 0 - 1, but values outside this range can occur

- A value of 1 means the predictions explain the data perfectly (predictions match the observations)

- A value of 0 means the predictions explain none of the variability of the data

- Negative values indicate the mean of the data provides a better fit to the outcomes than the predicted values

- Caveats

Applied Predictive Modeling page 96:

[…] the practitioner must remember that $R^2$ is a measure of correlation, not accuracy</br> $R^2$ is dependent on the variation in the outcome

Explained variance

$explained\text{ }variance = 1 - \frac{Var(y - \hat{y} )}{Var(y)}$

Where $Var(y-\hat{y} ) = \frac{\sum{(error^2)} - mean(error)}{n}$

According to this StackExchange answer the only difference between $R^2$ and explained variance is the mean(error). So if the mean(error) is 0, explained variance and $R^2$ will be the same. A more thorough answer can also be found on StackOverflow.

The Proposed Solution

RMSE and $R^2$ are the most popular measures according to Applied Predictive Modeling and Hands-On Machine Learning. In the spirit of getting a better intuitive understanding of the metrics, I’m going to run all of them and see what they tell me.

The Fail

The number of books and websites I had to go through to cobble together all this information was ridiculous. I expected it all to be in one place. Part of the problem was that most of the books I own spend more time on classification metrics. Part was that I didn’t remember things that the authors took for granted (thus the Concepts section). Yet another part was that the notation varied in some books. For example, the authors of The Elements of Statistical Learning obviously love mathematics way more than I do.

Getting better at reading math equations is a hurdle I’m going to have to tackle at some point. Eventually I should be able to read a change in notation without having to dig through the internet. All of which sounds like a great, extended, broken out by subject, topic for another (advanced) series of entries.

Up Next

Regression metrics - implementation

Resources

- Applied Predictive Modeling

- Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn & TensorFlow

- Understanding the Bias-Variance Tradeoff

- Residuals for Linear Regression Fit

- The Elements of Statistical Learning

- Errors and residuals

- What is the difference between errors and residuals?

- Mean Absolute Error

- Bias of an estimator

- Variance

- Standard Deviation and Variance

- Residual sum of squares

- Coefficient of determination

- What is the difference between 𝑅2 and variance score in Scikit-learn?

- Python sci-kit learn (metrics): difference between r2_score and explained_variance_score?