Entry 18: Cross-validation

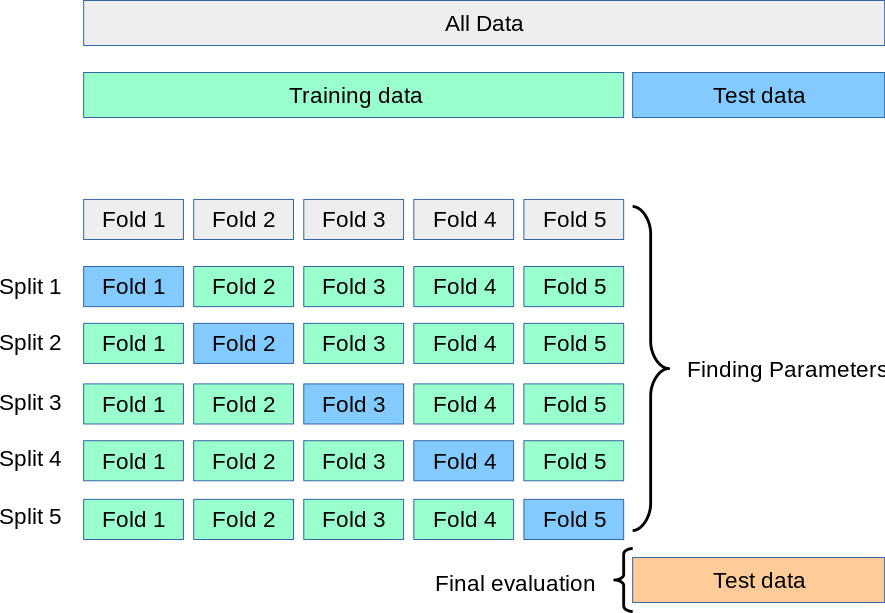

In Entry 17, I decided I want to use a hybrid cross-validation method. I intend to split out a hold-out set, then perform cross-validation on the training set. Scikit-Learn has a great chart of this hybrid method:

The notebook where I did my code for this entry can be found on my github page in the Entry 18 notebook.

The Problem

Now that I know how I want to split/sample my data, I have to decide which method of cross-validation to use.

The Options

There are quite a few variations of cross-validation. The major variants include:

- K-fold

- Leave one out

- Shuffle-split

- Repeated

K-fold cross-validation

The data is broken into k pieces (where k is a user specified number, usually five or ten). The model is trained on all k pieces except one, then tested on the final piece. This is repeated k times, at which point each of the k pieces has been used as the test set.

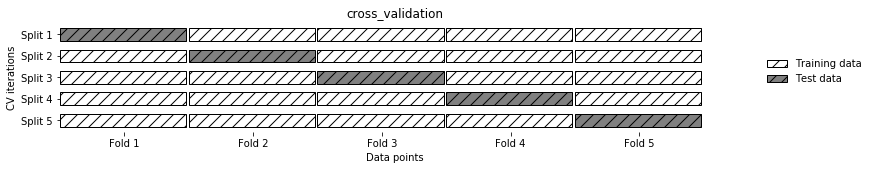

The Python library that was built to accompany Introduction to Machine Learning with Python, mglearn, has a good visual representation of this:

- Split: this is the row. Each split is basically just a replication of the full training set, it contains all the data. Each split is then broken into folds, or pieces.

- Fold: this is the column. A fold holds the same set of observations from one split to the next. What changes is whether that particular fold is allocated for training or testing. Every fold is approximately proportional to every other fold (i.e. in 5-fold, each fold would hold 20% of the data, in 10-fold each would have 10% of the data).

An Introduction to Statistical Learning says this about the choice of the size of k:

there is a bias-variance trade-off associated with the choice of k in k-fold cross-validation. Typically, given these considerations, one performs k-fold cross-validation using k = 5 or k = 10, as these values have been shown empirically to yield test error rate estimates that suffer neither from excessively high bias nor from very high variance.

Once all the k-fold models have been run and tested against their specific test fold, the performance of all models is averaged to produce an overall score.

When using this method, it is important to separate the training and test sets before any pre-processing. If pre-processing is done first, there will be data leakage. Data leakage happens when the model is given information it wouldn’t have had at the time of prediction.

For example, in Entry 8 I covered centering and scaling. Including the values from the test set would alter the mean which is used to center the values. This gives the model information it wouldn’t have had if pre-processing was done on only the training set.

I’ll cover how data leakage relates to data splitting in more detail in Entry 20.

When using k-fold cross-validation for classification, it’s best to stratify the classes so that the portion of each class is the same in each split as it is in the overall dataset. I covered stratification in Entry 17.

Leave-one-out cross-validation

Leave-one-out is very similar to k-fold. It works on the same principles, but only holds out a single observation as the test set. As such, it creates the same number of models as the number of observations.

This method can get computationally expensive really quickly. If the dataset is only as big as some of the toy datasets I’ve been using as examples, it should be fine. However, the training data for my day job regularly includes hundreds of thousands of observations, if not over a million (depending on the time range we train on).

Leave-one-out can easily be adapted to leave-k-out, where k is a user defined number of observations to include in the test set. This will reduce the computational expense. However, for the large datasets I’m practicing for, I’m leaning toward k-fold cross-validation.

Shuffle-split cross-validation

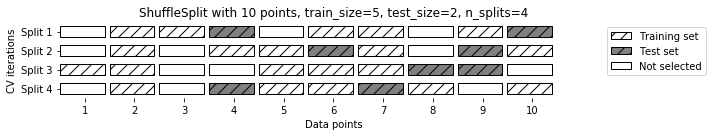

This method is similar to an iterative/repeated version of the hold-out method. The data is shuffled, then split into train and test sets. This is repeated a user specified number of times (called splits, just like with k-fold cross-validation). The difference between this and k-fold is that, as the name implies, in k-fold the data is broken into folds. Each observation is in one and only one fold. With the shuffle-split method each observation is chosen at random from the full dataset to be part of either the train or test set.

In Scikit-Learn there is an option to set how much data is used in train and test. This value can be set as an absolute number (specify exactly how many observations should fall in each, ex: 122, 13) or as a floating point number (specify the portion of the full dataset to use, ex: 0.8, 0.2). The numbers can be set to a value below the full dataset, allowing data to be left out at each split (ex: 0.7 and 0.1).

The mglearn library has a good visual representation of this:

This method sounds interesting, however, it is more difficult to use to assess model efficacy the way I want to. Each observation could get one, none, or multiple predictions for it depending on how often it ends up in the test set. This makes it more difficult to run the metrics listed in Entry 16.

Repeated cross-validation

Repeated cross-validation is exactly what it sounds like: repeat a cross-validation technique a user specified number of times. The key here is that each repetition has different folds. Between one iteration and the next, the data is shuffled and observations are put in different folds before the cross-validation is conducted again.

Supposedly this give a more robust model assessment score, but at the current stage, it sounds like overkill. I may try this at some point in the future to see if it’s any more accurate.

The Proposed Solution

Based on the definitions, challenges, and benefits of the four methods described above, my inclination is to use stratified k-fold cross-validation. An Introduction to Statistical Learning sites five or ten folds as having been empirically shown to ‘yield test error rate estimates that suffer neither from excessively high bias nor from very high variance.’

K-fold is computationally less expensive than leave-one-out, easier to turn into mathematical metrics than shuffle-split, and more straight forward than repeated cross-validation.

The Fail

After all the research on cross-validation (this is the third post about it after all) I assumed implementing it would be the easy part.

Up Next

Resources

- Difference in KFold and ShuffleSplit output

- 3.1.2 Cross validation iterators

- An Introduction to Machine Learning with Python

- An Introduction to Statistical Learning

- A Gentle Introduction to k-fold Cross-Validation

- Why use repeated cross-validation

- 3.1. Cross-validation: evaluating estimator performance