Entry 17: Resampling

I have no intention of simply training a model and calling it quits. Once the model is trained, I need to now how well it did and what areas to concentrate on in order to make it better.

The Problem

Once a model is trained I need a way to see how well it’s doing and be able to compare it to other models. If I evaluate the model on how well it performs on the same data it was trained on, this gives a very skewed view of model performance. The model could just have memorized the correct answer for each individual observation or there could be some fluke in the data that isn’t generalizable to new data points.

For example, if I create a model to predict the culprit in a game of clue, if my training data only has one observation with Col. Mustard, say he did it with the revolver in the library, then the model will assume that every time revolver and library is seen that Col. Mustard is the culprit. It just memorized the combination.

The Titanic dataset is a good example too. If the model has been overfit, it could just memorize that ‘Heikkinen, Miss. Laina’ survived. The model would score 100% on the data it trained on, but when presented with a passenger it has never seen before, I wouldn’t expect the results to be better than random guessing.

In the real world, I train a model, then set it free to predict on new data. As such, I can’t base my assessment of performance on data the model is used to. I need a way to gauge how well it’ll perform on data it’s never seen.

Definitions and Context

Generalization, overfitting, and underfitting

Definitions and discussion from Introduction to Machine Learning with Python by Andreas Muller and Sarah Guido.

- Generalization: when a model is able to make accurate predictions on unseen data it is able to generalize from the training set to the test set.

- Overfitting: when a model is fit too closely to the training set, but is not able to generalize to new data, it is overfit.

- Underfitting: when a model is fit too loosely / simply, causing it to predict poorly on training and test data, it is underfit.

Image from Train/Test Split and Cross Validation in Python

Andreas Muller and Sarah Guido link overfitting and underfitting with model complexity. An underfit model has too little complexity - generally not enough features to determine patterns. An overfit model has too many features.

However, they also point out that model complexity is strongly linked with the variety of inputs in the dataset:

The larger variety of data points your dataset contains, the more complex a model you can use without overfitting. […] collecting very similar data will not help.

Data splitting

This challenge is generally addressed by some variation of data splitting and model training.

- Dataset: the full set of observations

- Training dataset or training set: a group of observations, usually comprising 70-90% of the dataset

- Test dataset or test set: a group of observations, usually comprising 10-30% of the dataset

The simplest form of this is to separate out a test set and predict on those values after a model has been trained on the rest of the data.

The next level is to split the data into multiple groups and rotate which group acts as the test set. There are several variations on this, generally revolving around the portions of data in each split.

Two things to consider when splitting the data:

- Stratification

- Replacement

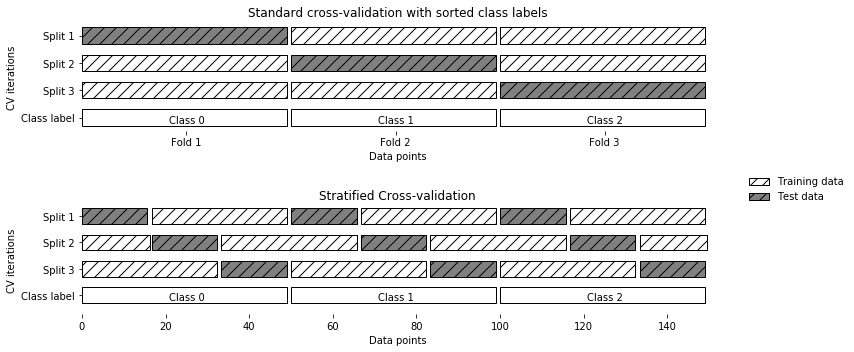

Stratification generally applies to classification problems. When one class is underrepresented the portion of that class in each group can vary drastically. The mushroom dataset was pretty even, 53.3% edible mushrooms and 46.7% poisonous, but stratification would ensure that ratio was consistent between the different data splits.

The example used in Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn and TensorFlow is the digits dataset. This dataset is comprised of handwritten digits from 0-9. If the numbers are evenly distributed (if there are ten 1s then there are ten 8s, etc) means that any one number only comprises 10% of the observations. If one of the digits is under- or overrepresented in any one group of observations, it can hinder the model’s ability to make predictions.

The purpose of stratification is to sample evenly from each of the classes to ensure even representation in each of the groups. For the example of cancer, if a positive cancer diagnosis is only 5% of the population, stratification will ensure that a positive diagnosis is represented as closely to 5% in each group of observations as possible.

The library that was built to accompany Introduction to Machine Learning with Python, mglearn, has a good visual representation of the difference between not stratified and stratified:

Replacement is whether an observation is allowed to be chosen more than once. One of the podcasts I’ve listened to in the last three years (probably Linear Digressions or Data Skeptic) used the analogy of a bag of marbles. Say there is a bag of marbles and it will be used to make a list of colors. Choosing marbles with replacement means that once a marble is chosen from the bag, the color is added to the list, then the marble is replaced in the bag for the potential to be redrawn. Without replacement would be to pull the marble from the bag, note the color, then put it to the side so that it is unavailable to be redrawn.

Most methods of data splitting is done without replacement.

The Options

There are multiple methods of using data splitting to evaluate models. The three main options are:

- Validation / Hold-out

- Cross-validation

- Boosting

Validation / hold-out set

The first obvious solution is to split the data into two parts: one to train the model and the other to test it once it’s been trained. This is a very common practice, the two portions of data are called the training data or training set and the test data or test set. By separating the train and test sets first, a set of observations that the model has never seen before are reserved and can be used to approximate how the model will perform on unseen data.

Drawbacks

- Limits the amount of data available for training (most models prefer more data to less)

- Highly dependent on what data is placed into the training dataset and what data is placed into the test dataset

Cross-validation

The solution to the two drawbacks listed above is called cross-validation. In cross-validation the data is split repeatedly and multiple models are trained. This statistical method allows a more stable and thorough evaluation of the model’s ability to generalize to new data.

Benefits

Full use of data

Cross-validation allows for better use of the data without sacrificing the ability to determine performance. In five-fold cross-validation 80% of the data is used for training and 20% for testing in each split. If expanded to ten-fold cross-validation 90% of the data is used for training and 10% for testing. Because every observation is used in the test set at least once, there is no penalty for the reduction in the size of the test set.

Alleviate dependence on data partitioning

Dependence on what data is placed in the train and test sets is alleviated with cross-validation by reducing the likelihood of clumped data. The example given in Introduction to Machine Learning with Python is observations that are easy to predict and ones that are hard.

Some observations will naturally align more closely with observable patterns. Others will be more difficult to classify. If all of the borderline observations are in the training data, then only easy to classify data will be in the test set. By splitting the data multiple ways and repeating the training and testing, each observation will be in the test set at least once.

Discern model sensitivity to data

Another benefit of cross-validation is information about the model’s sensitivity to the selection of the training data. The range of accuracy scores is an indication of how large an effect changing the observations has on the model. A narrower range indicates insensitivity to changes in data, whereas a large range indicates high dependence. It also gives an estimate of best and worst case performance when applied to new data.

Bootstrap

Bootstrap is random sampling of the data with replacement. Since any observation can be chosen more than once, the sample size can be the same as the full dataset. The observations that aren’t included in the sample (called ‘out-of-bag’ in Applied Predictive Modeling) serve as the test set.

mlcourse.ai had the best visualization of this method I could find:

To me, this method feels like a variation on cross-validation. However, Applied Predictive Modeling and An Introduction to Statistical Learning both list it as a separate method.

Boostrap tends to have less uncertainty than k-fold cross-validation, but the bias is similar to k-fold where k=2. It can be problematic on small datasets and tends to be overly optimistic when the model has overfit the data. Small datsets aren’t a problem on the data I use at work, however it is a problem on the toy datasets I’ll be experimenting on.

The Proposed Solution

The hold-out method doesn’t provide a robust enough solution for what I’m interested in. Bootstrap seems to have more problems and caveats than it’s worth. Cross-validation is robust and has the implementation flexibility to address various concerns with data size and class imbalance.

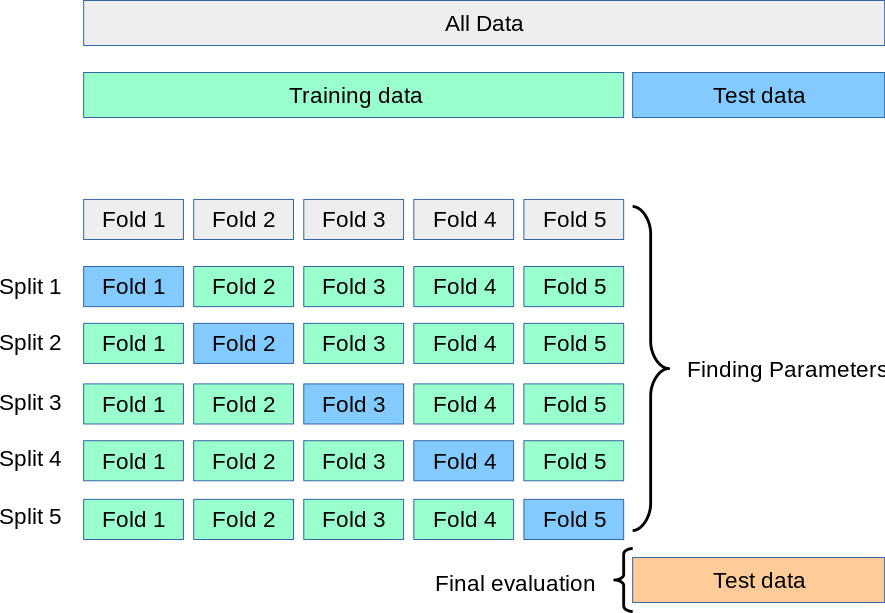

I’d like to take cross-validation one step further. DataRobot uses a hybrid approach that combines aspects of a single hold-out set and k-fold cross-validation. They separate out a test set, automatically run cross-validation using the training set, then allow validation using the hold out set on a model by model basis. This is also the strategy recommended by Scikit-Learn on their cross-validation page:

This hybrid method, where the test set is separated and left untouched, then k-fold cross-validation is run on the training set, seems like the most robust solution. It allows me to tinker with hyperparameters and examine the cross-validated scores while still having a hold-out test set to compare against once all the fine tuning has been completed.

The train_test_split function in Scikit-Learn’s model_selection module will split the data into the train and test sets. It automatically shuffles the data. The shuffle is necessary in case the target class has been ordered (ex: home prices are in ascending order or all poisonous mushrooms are listed last).

The Fail

Initially, I thought I could just use the KFold or cross_val_score functions from Scikit-Learn. However, per Introduction to Machine Learning with Python, the cross_val_score function isn’t a suitable way to build a model that can be applied to new data. Calling cross_val_score from Scikit-Learn builds models internally for the sole purpose of evaluating how well a given algorithm will generalize after being trained on a specific dataset.

The main problem with this is that for cross-validation to be free of data leakage, any pre-processing step that aggregates the data needs to be done on only the k-fold it’s training on. This means that centering and scaling steps, categorical encoding, feature selection based on correlation with the target, and other pre-processing cannot be done ahead of time.

Basically, the quick and easy option isn’t actually an option.

Fortunately, Scikit-Learn’s model_selection module has many different options, several of which seem viable for the express purpose of running multiple metrics to see how well a model is performing. There are also a plethora of options for variations on cross-validation, which warrant their own full entry.

Up Next

Resources

- Introduction to Machine Learning with Python

- Train/Test Split and Cross Validation in Python

- A Gentle Introduction to k-fold Cross-Validation

- 3.1. Cross-validation: evaluating estimator performance

- Why every statistician should know about cross-validation

- Cross Validation Gone Wrong

- Applied Predictive Modeling

- An Introduction to Statistical Learning